“Only a blinking eye can measure the light” —Sandra Beasley

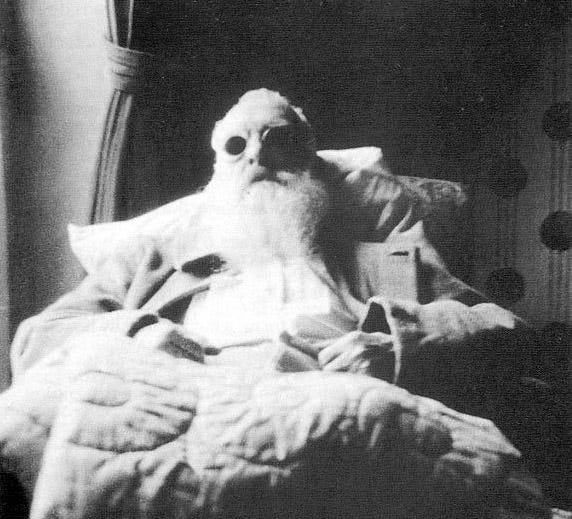

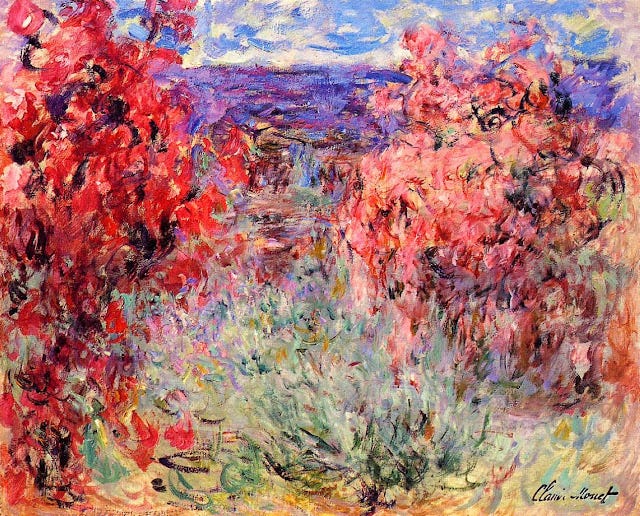

Imagine you’re almost 80. Your eyes are so clouded by cataracts that you can no longer see greens and blues but more of a muddy mass of browns and reds and even things that should look white have a yellowy tinge. Now imagine that you are one of the most famous painters in the world and it’s the middle of the First World War and the president of France has commissioned a giant wall-sized work of radically abstracted waterlilies and you are terrified of surgery because you saw your friend Mary Cassatt go blind and completely give up painting. In 1905, Claude Monet noticed his vision getting worse, by 1914, he was painting in the gentler light of dusk and dawn, by 1918, he was choosing his colours not by what they looked like, but by the names on his tubes, and painting scenes more from memory than from life. In 1922, Monet was legally blind. Finally he decided to have the surgery. But just on one eye. I don’t know if it’s the paintings that came out of Monet’s struggle to see form and colour in his fading vision, or his new octogenarian lease on life after the surgery that made the better paintings. But there is something in later Monet that feels like a bridge between nature and spirit, between landscape and pure abstraction. Plus once his eye healed and he had the right glasses and the cataract was removed along with UV protecting lens of his right eye, he was able, like a bee, to see all the invisible ultraviolet patterns in his world.

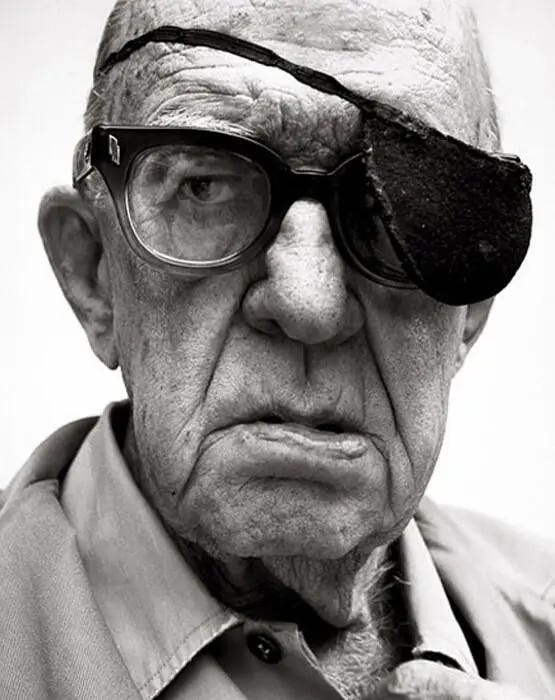

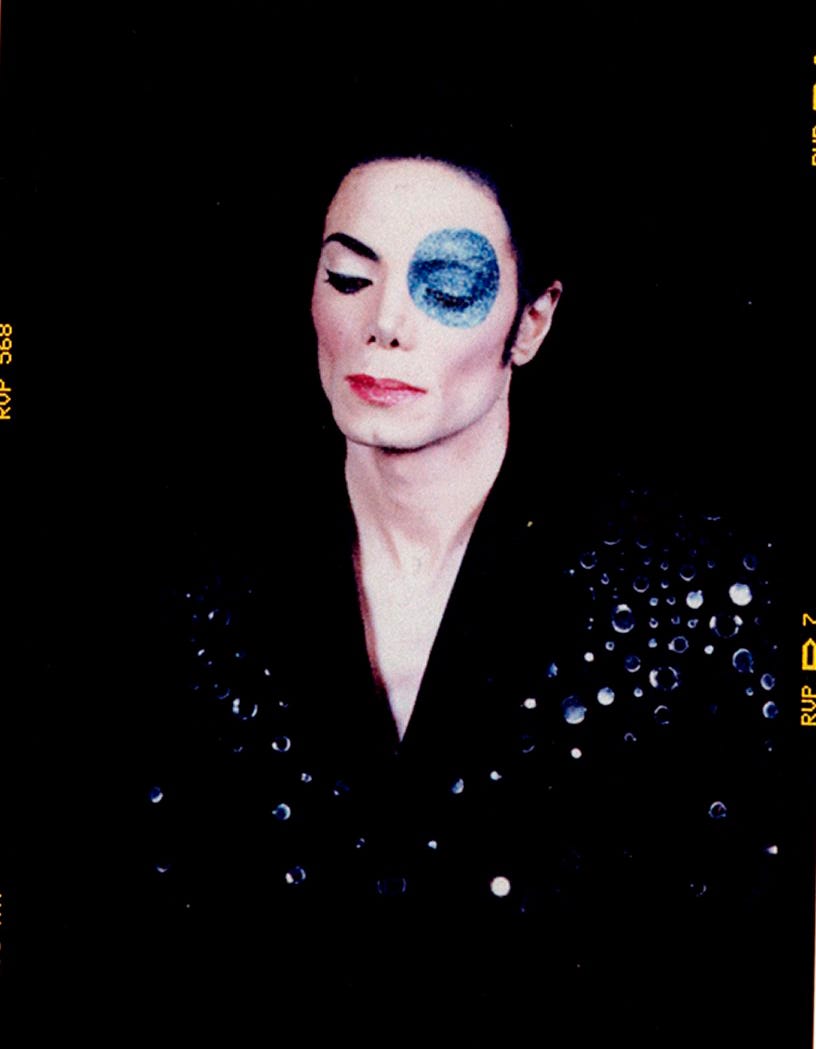

I have been (very slowly) reading The Master and his Emissary by Iain McGilchrist, a book of neuroscience and brain mapping-meets-philosophy and ways of experiencing the world. It seems also to explain a few things about the sort of overly algorithmic way of seeing we invented out of necessity and then trapped ourselves in. It’s also about the right and left side of your brain which got me wondering if you could circumvent your logical brain by just looking out of one eye, and I was testing this idea out in the woods trying to just feel instead of think which is hard to will yourself to do even with one eye closed, and then I started thinking about eyepatches and once you get the Lauren Hutton eyepatch photo in your head it’s hard to get it out of your head, which lead me to Monet and his superhuman eyes making tangled scenic images that were a kind of tunnel into abstraction.

The full eye-patch photoessay is available for members of the lab (plus a strange experiment that shows how much of what we calling seeing is a strange collaboration between our brain and the world). But for you dear free Colour reader I offer this:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Colour | Newsletter | Lab | Community to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.