My Papa had the sturdiest back, the darkest beard, the curliest black hair, the strongest arms, the darkest olive tan all through the summer, the deepest voice when he sang with his guitar in church, the sweatiest dress shirt tucked into old jeans, and he was the wildest Papa. We would beg him for the Draper Lake Express. On certain special nights if we asked enough times after we’d all been bathed and the the summer night was slightly cool but not cold, he would somehow get all 4 of us on his back and shoulders, and the littlest one (Leah), held like a dufflebag under his arm. He would then run crashing though the woods down the little path, past the cold spring, past the pink granite rocks rounded and ancient and almost hidden in the undergrowth, children hanging on for dear life. He was fearless as a goat but breathing heavily like he was almost going to drop one of us. We all were in our pyjamas, mine were blue and purple striped flannel, so old that they were like a dog chew toy, and no shirt and a clean white flannel cloth for our wet hair, and you could feel the warmth of all the kids. And we all knew that path and we were all laughing, and then we were at the lake and we would all tumble off the Papa freight train, the lake black and round and ageless under the night.

A trout lived at the very bottom of this deep lake. The lake had a little island where once Papa had leaped off a mini-cliff and broke his toe trying to save Leah who had fallen in as a toddler but who was swimming just fine without any help. Our personal island. The lake was so deep and round and weedy at the edges, and calm and lapping its greenblack liquid liquorice colour, and it was our lake because our house was the second last house on the little winding country road, and the last house was the Shepherd’s. They had been there for four generations and would buy up any property that was for sale anywhere near the lake so that it would stay farming land and not cottage people from some city. And so the lake seemed ancient, archetypal, complete, so round that it was rumoured to be made by a meteorite sometime at the beginning of time. The landscape around this lake was where the hill of bloodroot we rolled down and practiced flying lessons was. Where Mama’s breadboard made of a piece of white grey marble we found and later would be her gravestone. It was where we collected snow and Mama made snow-mixture and found and let go of a tiny painted turtle.

It was that lake that was the last stop on the Draper Lake Express. And at the end of the path at the edge of the lake there was a tiny snailshell beach that almost glowed at night, the colour of the moon. We looked out over the lake still flushed from hanging on like possums and laughing along the bumpy ride. Papa was strong but the ride was always on the verge of collapse. The snailshell sand glowed iridescently. There was a half-sunken row boat parked in the sand, an only partly successful carpentry project of Papa’s. We did not dare to go into the lake, even on hot nights, because of the weeds and the leeches. A light wind made me shiver with my wet hair. I think we must have walked back. Papa finally exhausted. Maybe Leah got to ride on his shoulders. Until the next time we heard, All aboard for the Draper Lake express, in his deep booming voice.

This last week I took a roadtrip to Draper Lake. Papa is in a respite-care home. The road into Draper Lake was still magical and winding and timeless, pot-holed gravel curving around bends and up and down hills through rocky landscape and over marshes, and past the house where the twin brothers lived into their nineties, and the house the witch lived in temporarily collecting dew drops from woodland flowers, and the house with the girl whose hair and face had been burned so badly that I was afraid of her sitting beside me on the school bus, and the other kids bullying me even more. The hillside where my Papa had once sawed down a Christmas tree for us but not knowing really how to saw down a tree so the pine tree divebombed off the cliff and its point cracked right off, and so that year he dragged home a kind of wreckage of a tree and we had the wildest middle of a Christmas tree and we loved it.

The gateway to the Shepherd’s farm at the end of the road followed by other gates further back, and the furthest back road was so rutted that you needed an all terrain vehicle to get back there, past the raspberry bushes and current bushes, and henhouse, and honey-making house, and the barn with the cows. Back behind all that, the Shepherd’s property backed onto the huge provincial park. There must have been twenty tiny lakes, some of them without names, hiking and camping and fishing for days, sleeping on the ground, soft and thick with pine needles. Cornbread baked in a stove made out of stone, the dragon flies the colour of a sparkly blue electric guitar, and faster than the mosquitos in and out of woodsmoke like tiny prop planes.

Back on our property there was a natural ice-cold spring my Mama found coming out of the ground below the house. We drank from it, ice medicine. She found the spring but now, just this last week exploring it with Lux, it had changed. Now it came out of a little cave that looked ancient with a tiny gateway made of mossy limestone. The spring, it seems, came from under the house. Maybe it was alway there but under grass uncovered further by some newer inhabitant of the house.

There was the grey barn already old when we knew it and now slumped and ancient but still with a shiny lock on the door. The locked door that we used to be small enough to slip through and in that mote-filled hazy world, slats of light a stagecoach and whips and piles of old old fairytales with strange Victorian pictures of spiders and woods and fairies. And the creepy pigsty below. And what was that barn now? Forty years later. But it was double locked and no way in other than crawling below through the scary old pigsty. In the yard beside the barn, at the fence a rusted metal canister with handles on both sides that I remembered right away.

When it was less rusted it held the chicken feed. It was my job to feed the chickens. You had to get past the wasp’s nest under the old grey stairs, but then you were in the coop with the clucking and feathers and scratching of chickens, and sometimes a still warm egg in the straw so exciting to find. Sometimes two or three in the nest. I remember being eight years old, I had a plastic scoop that was a bleach bottle cut in half, and when the feed was low, I would have to tip my whole body into the metal canister, my feet leaving the hay strewn floorboards of the chicken coop, the canister dark and echoey, the pellets of green-grey chicken feed smelling wholesome like dry grass and bran flakes. The pellets were a bit shiny on the outside, the pellets in the metal can clicked against each other when you dug the scoop in, chickens clucking with hunger in the background. I reached deeper in to completely fill the scoop. It was cold in that metal canister, its edge was smooth and sunk into my stomach, the smell of grains and the cold and the clucking and the slightly sick feeling in my stomach that the lip of the feed barrel gave me, the sort of sick feeling in your stomach you might get knowing that something scary was going to happen or knowing that you were going to fall in love, even the stomach feeling of embarking on an adventure that you could not see into but that pulled you forward. But I was eight and I did not know what all the meanings of a slightly sick feeling in the stomach could be.

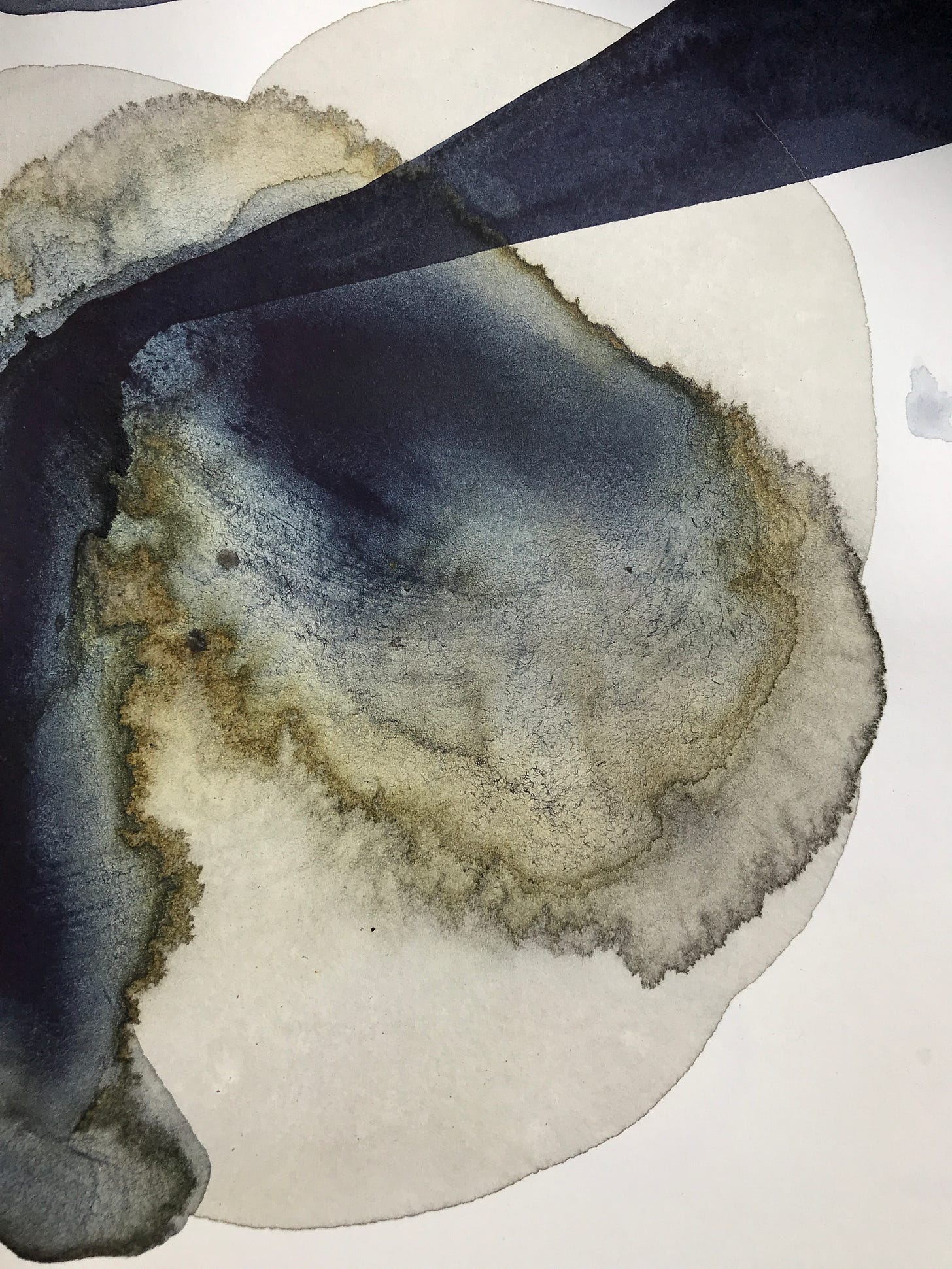

Back at the lake in the present, the current owners of the house had torn up the old Draper Lake express path and the once-hidden pink Canadian Shield rock were more exposed. They had put a container of an old transport truck down by the water and old tires that acted as a bridge. But the Lake! It looked beautiful in the sunset. I took off my shoes and socks and walked into the shallow water forgetting the leeches. It was cold but not freezing. The snailshell sand was still there soft and prickly at the same time. A tiny beach just a few metres in total. The water lapping. Our own little island now had a cottage on it. But it was so still. So quiet there. And good. I scooped up a handful of the sand and put it in a container with water from the lake.

This would be the first ingredient for the project.

Its a project that is a sort of hour glass of family, colour and memory. A project for movements, suspensions and circulations of materials that will in a looped brotherhood of glass. A project of mud and sparkles, heart and science, medieval humours and mystery broken up and reassembled. A project of circular becomings. Next week I will write to you about the second ingredient. And after that I want to explain the steps of construction to you as it becomes a real thing in the world, dear readers. As always thank you for supporting The Colour.

.

I always feel like I am there in your story. Maybe parts of your writing just resonate with everyone who reads your newsletter. I’m glad you went back to the lake. When we were young we’d be in the backseat of the car and it was always my biggest thrill to see the water. It wasn’t always the same lake but often Lake Erie. Lake Ontario was seen every day (but just part of the view, taken for granted). Thank you for the stories and the colour.

I hope your Papa is getting very good care.

As always, your writing stirs up so much. I've been thinking of writing An Account of my Life, so I don't forget things, just for myself. Last week, I had the sudden memory of me chasing our sheep called Cubes down a red sandy road - he always got out of the stables and I was always the one who had to go and get him. I was about eleven at the time (we lived in the country about an hour and a half north of Johannesburg, on a kind of ramshackle but wonderful small holding).

We had just fed the horses and, being South Africa, it was always dark that time of the morning. And there I'd be, in my school uniform running down the road after Cubes. You'd have thought we'd have found a better way to keep him from getting out but Cubes was an escape artist. He slept in the stables with one of the horses to stop him from pacing around all night. The theory was that Cubes would wander in the horse's way and stop him from circling. I think maybe Cubes just lay down in a corner, out of the way of the pacing horse and then made a wild dash for freedom the minute we opened the door.

I'll be honest, I hated getting up in the dark and trudging through the condensation soaked grass (I don't like getting my feet wet) and mixing horse food with water (more wet!). But now, when I get a hint of any smell like it at all, of those cool dark fragrant mornings, it makes me so happy and I wish I could be there again, with my sister and my mom and dad who were such adventurers (and later moved us to two rooms in a veldt with no electricity or running water, to 'get back to the land'.)

I remember feeling so happy and powerful because I was the one who could get Cubes back. In my pale blue school uniform and striped blazer, I would grab his thick curly fragrant hair and lug him home. Our animals were a bit of a revolving door and I think we sold the horse along with Cubes (they came as a couple).

I am hoping (selfishly), that maybe one day you'll collate all your posts from this into a book because they are such wonderful memory prompts for me and I'd love to read them all again.

My childhood was not easy by any means. But it was unusual and with that, comes so many gems and I want to dig them out and collage them into a book, if for no one but myself. I've always felt like an outsider but not in a bad way, more in a self-contained way and your posts remind me of those self-contained moments of joy - and all of them, linked to nature and the wondrous smells, of jasmine, horse droppings, we grass, the rich horse food, and that incredible South African cool, fragrant air that I miss with all my heart. Thank you!