Sudden Red

The Life and Death of Fall Leaves

“…the thing itself always escapes.”

― Jacques Derrida

Red, I said. Sudden, red.

— Robert Haas The Problem of Describing Color

I didn’t think I had much to say about fall colour, I kind of associate it with the funereal covers of photocopied Christian service pamphlets, the kind with an image of path into the woods or a covered wooden bridge in Vermont. I kind of remember feeling something, crammed into the back seat of the buttery yellow-and-wood-panelled Jeep Wagoneer with my brother and sisters, and my Papa saying, O man look at that colour! as we rounded a hill on a wrong turn on road trip to who knows where. But I think I was feeling more a wave of carsickness than a wave of joy at the colours of nature.

What I remember better is raking up a huge pile of fall leaves and jumping into them. The way the tones of brown and copper and gold and the crinkly sounds and earthy spicy smells and crumpled-paper gentle prickle all softened together to let you jump in. Sinking in laughing with your sister and with all of your senses and the golden bits, and feeling it flying like confetti around you and stuck in your sweater and hair until almost you become that pile of leaves. I guess I liked being in it. Fall colour just seemed like a postcard, or an image framed by the window that doesn’t open all the way.

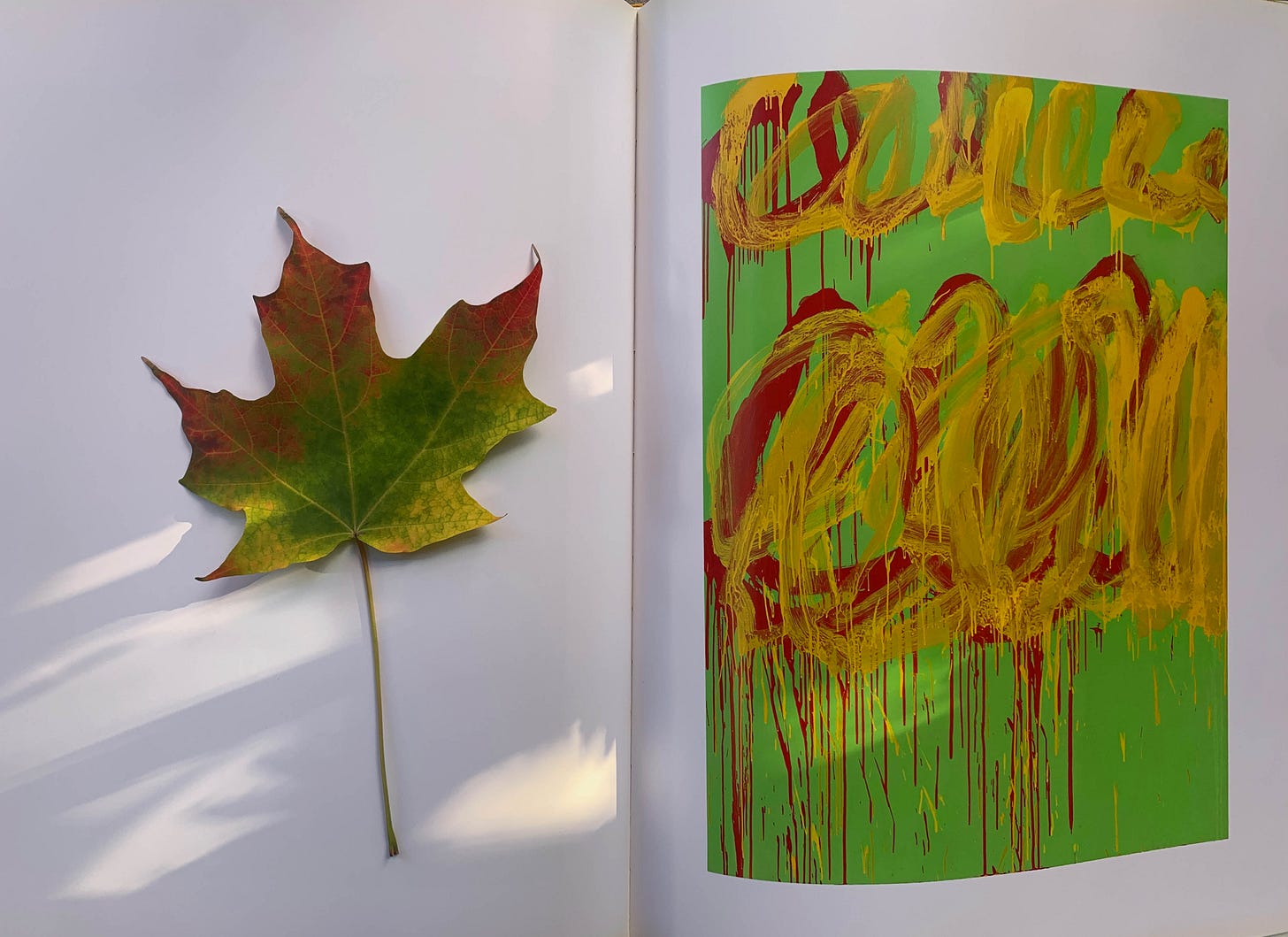

Still, I was thinking of the colour of fall leaves on our last photoshoot in New York for the Colour Wizard book when I found myself working with a bilingual forest school in Queens in a park I had never heard of. We were deep in the woods and I didn’t have much of anything in my backpack except a hole punch and a piece of charcoal and besides that, my incredible stylist Jodi had moved on to her next job and the uHaul van was returned, and all of my bags and paper and tools were over in the East Village, so we were forced to make colour magic mostly with what we could find on the ground. We searched for magic wands of vines and twigs and lichen-speckled sticks. We wrapped a piece of paper around a tree and painted it with the last of the pokeberry juice and charcoal ink ground-up in a plastic container that once held seaweed snacks. We even found some tiny yellow-green fuzzy oak galls which we didn’t have time to make into ink but which looked great tucked into a miniature empty Altoids tin. We also collected leaves, and I found myself really noticing the way I was asking the kids to notice, and I started to see each changing leaf as a kind of ink test. Like each leaf was was a piece of paper registering a moment in time and a set of conditions: moisture, temperature, soil, air, and light.

There is of course a whole economy around peak leaf colour prediction. Cold but not freezing nights and not too much rain and a good spring and summer, and low levels of pollution in the air and soil all lay the groundwork for the best fall colour. But leaves being creatures of light take their most powerful cues from the sun. When the angle of earth is tipped just right, some ancestral part of the leaf tightens veins and slows production and breaks down chlorophyl and pulls nitrogen back into stems and branches and says to itself, it’s time to let go. In this complicated end-of-season choreography, the green chlorophyll so essential for energy and growth fades away to reveal all the other colours that have been working away inside the leaf. And this explains the yellow and and oranges the gold and the brown of fall leaves.

And then there is red. The red of autumn leaves comes from anthocyanin pigments which are probably the most important source of colour for the natural ink maker and, unlike the yellows, they are not being unmasked in fall. They are created at the end of a leaf’s life. The red colour is produced by sugars in the tree and the pigments signal to birds, insects, and other animals, while its chemistry is acting as an antioxidant counteracting the unstable atoms, protecting the dying leaf from radiation and doing some amazing work with nitrogen to close down the cellular energy factory without waste. When these red pigments mix with yellow they create orangey tones when they mix with green they can go purple or almost black, and then eventually the reds fade with the the UV light and the leaf colour left is the brown of tannins and finally the almost white of the ghost leafs you sometimes see in a winter forest curled like a chrysalis.

And so the colour includes the whole tree’s record of its transformation. A record of holding on and letting go. Get close to a leaf and you can feel the intricate almost infographical patterns of greens, yellows, browns, and reds. Get close and notice where its has been eaten by bugs, curled by the cold, and torn by the wind. Right now the leaves are falling, the world is dying, and in its dying it is beautifully alive. And if you can see it that way, it feels not like a postcard at all, but like you are in it.

In the Colour Lab this week (Subscribers only)

A single fall leaf also happens to have what are probably the four most important pigments for making natural colour. Its really hard to isolate anything from fall leaves other than some tea-coloured tannins but they present in one place an almost full palette of natural colour. So with an understanding of these 4 basic pigment types you can make thousands of kinds of ink.